Itzhak Perlman shares advice, adventures during student session

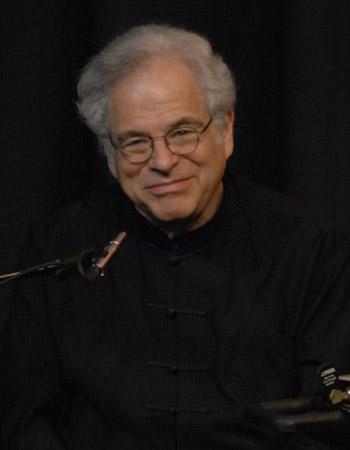

Itzhak Perlman, internationally celebrated concert violinist, soloist, teacher and conductor, spoke to an attentive standing-room-only audience of music students in the Rothwell Recital Hall on Thursday, Oct. 6. Later that evening, Perlman would speak before a much larger public audience as the 12th in the Judge Joe J. Fisher Distinguished Lecture Series.

Itzhak Perlman, internationally celebrated concert violinist, soloist, teacher and conductor, spoke to an attentive standing-room-only audience of music students in the Rothwell Recital Hall on Thursday, Oct. 6. Later that evening, Perlman would speak before a much larger public audience as the 12th in the Judge Joe J. Fisher Distinguished Lecture Series.

Perlman is known for his ability to evoke emotion and lyricism from his violin, making deep connections with his audiences. Since he first asked his parents for a violin at age three, he has become one of the most well-known and respected instrumentalists in the world.

A recipient of the 2008 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, four Emmy awards and the Presidential Medal of Freedom among countless others, he answered a broad range of student questions between telling stories, discussing his career in the context of a changing music industry and, most of all, extending advice.

A recipient of the 2008 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, four Emmy awards and the Presidential Medal of Freedom among countless others, he answered a broad range of student questions between telling stories, discussing his career in the context of a changing music industry and, most of all, extending advice.

“The trick with playing music is to find your voice,” Perlman told the students. “You have to have a passion there and a love—you also can’t admire only one performer while you’re nurturing that love, or you will forever emulate them. You need to have something to say; say it.”

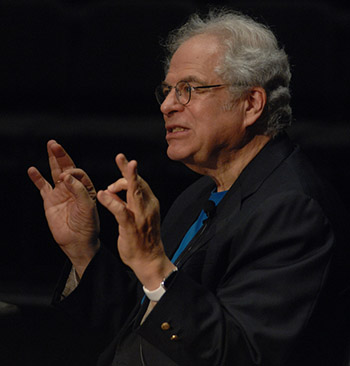

His booming voice and quick wit in extending such advice reached even the farthest reaches of the room, while his unpretentious appearance—gray curly hair, glasses, blue tee—eliminated the barrier between himself and the crowd. Although a table was originally set up, Perlman opted instead to sit, unobstructed, in front of the audience next to moderator Brian Shook, interim music chair.

As student questions were read by Shook, Perlman listened carefully, then answered enthusiastically, gesturing emphatically.

Throughout the session, Perlman stressed the importance of fine-tuning one’s listening skills as they progress with their instrument – and with their life.

“I play, I teach, I conduct. No one is more important than the other,” he urged when a student asked about his favorite ‘job.’ “They all require a great deal of skill in listening. The better you listen, the better you play. When we teach, we have to listen in a very specific way; we have to listen to ourselves.”

“I play, I teach, I conduct. No one is more important than the other,” he urged when a student asked about his favorite ‘job.’ “They all require a great deal of skill in listening. The better you listen, the better you play. When we teach, we have to listen in a very specific way; we have to listen to ourselves.”

At the age of four, Perlman contracted polio. The disability subjected him to a life of mobility aids and a long line of doctors, but gave him the opportunity to focus on his craft as he practiced, on average, three hours daily. Although he admits practice could be grueling as a child, he stressed the old adage, “practice makes perfect.”

“[My parents] did have one idea about how I was practicing, and that was that you should not hear an empty space,” he said later in the evening lecture after Kevin Smith, senior associate provost and lecture moderator, recalled an earlier student question. “In other words, if there was no noise, it was no good.”

Perlman admitted, smiling, that he later found a way around that. When introduced by a doctor to the Feldenkrais method of gentle movement and meditation, he would tell his mother in moments of silent boredom that he was practicing—via the Feldenkrais method, of course.

After telling of his move from Tel Aviv, Israel to New York at age 13 to continue his studies and being suddenly thrusted into the international performance circuit following an appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1958, a student asked Perlman if he still gets nervous about performing. He laughed.

“Yes, absolutely,” he said. “When you’re really young, you don’t get nervous because you don’t know what it’s really about. You’re not smart enough to get nervous. Then something happens and you think, ‘Ah, now I’d better get nervous.’ A lot of kids ask me what you do for nerves and I say, ‘There’s no such thing.’ The only thing is to be aware of it. Know that it’s coming. Know thy enemy.”

“Yes, absolutely,” he said. “When you’re really young, you don’t get nervous because you don’t know what it’s really about. You’re not smart enough to get nervous. Then something happens and you think, ‘Ah, now I’d better get nervous.’ A lot of kids ask me what you do for nerves and I say, ‘There’s no such thing.’ The only thing is to be aware of it. Know that it’s coming. Know thy enemy.”

He told of a fellow musician plagued by nerves with whom he had toured. Before every performance, the musician ceremoniously consumed a Hershey chocolate bar, a Coca-Cola and a cheese sandwich.

“It would get very difficult when we were in other countries to feed this habit of his. I had another friend who would just throw up every time a performance was looming, then say ‘Ok, I’m good to go.’ As for me, I get nervous, I process it, I go ‘Blah!’,” he said, flailing his arms, “Then…I just play.”

And play he did, masterfully, later in the evening’s lecture. Between telling stories from his youth, he performed Johann Sebastian Bach’s Gavotte en Rondeau, which he played in a commercial for an Israeli cookie company, and one half of Henryk Wieniawski’s violin duet, Caprice in A Minor, which he played during his 1958 debut on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

After teasing that the audience reaction was overly polite for the Bach piece, his fast-moving, emotional rendition of Wieniawski was met with thunderous applause and a standing ovation.

A student asked if he could cite one stand-out, influential performance he had either seen or played himself. He thought for a moment.

A student asked if he could cite one stand-out, influential performance he had either seen or played himself. He thought for a moment.

“I think in every performance, I get moved by the music and I just hope I can do it justice—I am affected deeply by my feelings,” he said. “I don’t think there’s just one influential performance. But my most memorable personal performance was playing Igor Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto in D in front of Igor Stravinsky. I still have a picture of Stravinsky and me in Honolulu with leis on.”

Going forward in the student session, Perlman contrasted different concert halls worldwide and various orchestras he’s worked with. He discussed his hobbies and admitted he hates travel.

“I mainly remember places—if I remember them at all—by what I ate there,” he laughed. “I like sports, dogs, and eating. I also enjoy seeing concerts, movies and baseball games. Public speaking is fun, too.”

“I mainly remember places—if I remember them at all—by what I ate there,” he laughed. “I like sports, dogs, and eating. I also enjoy seeing concerts, movies and baseball games. Public speaking is fun, too.”

After a student asked if he believes it’s important to learn the context around a piece, Perlman said it helps more to understand the preferences of the musician whose work is being played.

“You can ask yourself, ‘Does it help that Mozart wrote this piece at the time he was writing his operas Don Giovanni or Magic Flute?’ Absolutely it helps,” he said. “Knowing what Mozart was really enthusiastic about – opera – helps me play a Mozart violin concerto. Opera was ‘it’ to Mozart. So everything that you hear from Mozart sounds like an opera. It sounds vocal. It does help, when you want to play a phrase, to ask yourself: how am I going to ‘sing’ that phrase like Mozart would?”

According to Perlman, the key to his success and his continued adoration of the violin has been resisting boredom. He said that going forward, he hopes he can approach all pieces—even those he has played countless times—with excitement. This hope is the only thing left on his bucket list (except for the bucket, of course).

“The key is to never be bored,” he said with urgency. “Find something that interests you in particular. It’s a challenge, but you always have to be interested in what you do—what may be one way today might become different tomorrow. Be inventive. Assess yourself. Do you love music? Do you have a passion? The worst thing is to feel that your music is a chore. Don’t get caught thinking you have to do something specific, or in a specific way. Do it your own way.”