Archivist reminisces on LU sailing program

When one thinks of a library archivist, they probably picture someone peacefully wandering among stacks of books, each containing tales of excitement and wonder.

That’s not the case for David Worsham, though, as the man amidst the stacks has his own stories to tell. He’s no pirate, but as a younger man he spent time sailing the high seas of Sabine Lake, pulling sunken boats up from the muck, and narrowly escaping nefarious crews.

Worsham attended Lamar University from 1983 to 1989, though he didn’t discover the sailing program until his third year at the university in 1985.

At the time, all students were required to take a physical education credit. The course catalog included options such as dance and strength training, as well as various sports. However, one in particular caught his eye — sailing.

“At the time, I said, ‘Man, that sounds like fun,’” Worsham said. “Now, I’d never sailed in my life, but I wanted to learn how to do it because I liked being on boats and I enjoyed being on the water. So, I signed up for the class and I was hooked.”

The sailing program educated students on the basics of seafaring, such as how to flip a capsized vessel and the logistics of tying many different sailor’s knots. They even began their course with basic swimming lessons in Lamar’s recreational pool.

Eventually though, amateur seafarers had to practice what they’d learned in the real world. That’s where LU’s recreational sports department came into play.

At the time, the university rented several boat slips located a short drive away on Port Arthur’s Pleasure Island. Students in the sailing program, those who had already completed it, and as students with an equivalent sailing certification, were allowed to take the boats out — much like how today’s LU students can borrow sports equipment from Outdoor Pursuits in the Umphrey Rec Center.

Worsham ended up working for the recreational sports department, where he was in charge of maintaining and supervising the school’s watercraft on weekends.

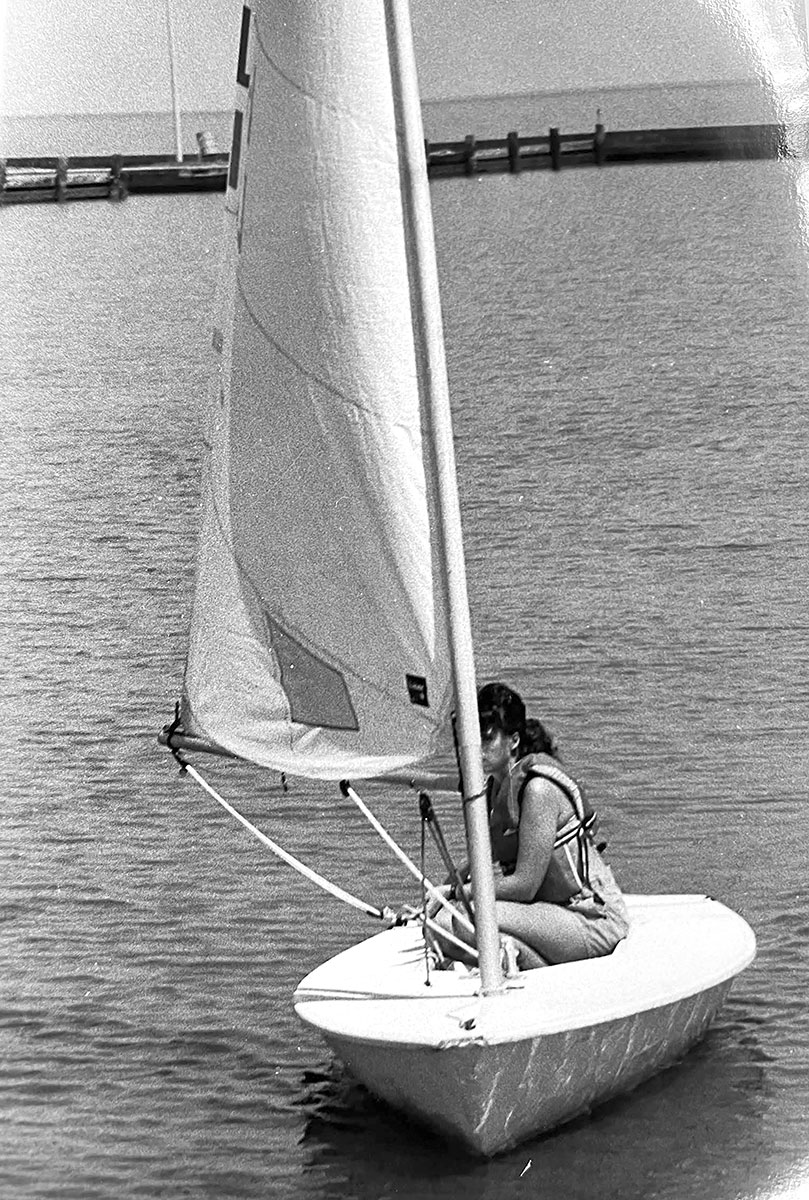

Lamar’s sailboats weren’t the most impressive vessels, Worsham said, but they were enough to stay afloat and have a good time on the water. The fleet comprised six 14-foot “lasers,” which were similar to the boats used in Olympic sailing. They were rather small and intended for just one passenger, though Worsham said two people could sail together if they were willing to get very friendly.

Student participating in craft class for credit from

Lamar University’s special collections department.

“These lasers were actually race boats,” Worsham said. “I would practice with the sailing team. They would come out to practice, and I’d get out there and I would race against them, kind of like having a sparring partner.”

The aforementioned sailing team was a short-lived effort by then-sailing instructor Bill Worsham (no relation). The instructor had a vision of a Division I sailing team which would compete against other universities. However, a lack of interest in competitive sailing, along with a shortage of funding, meant that the sailing team never truly took off.

Despite the disappointment in the competitive sailing scene, David Worsham said Lamar’s sailing program and boat rentals were fairly popular. Thanks to his years working for rec sports, he had plentiful opportunities to get out on the water, along with many stories to share.

While he was still quite new to his job, Worsham made a costly, albeit comical mistake. See, these boats had what was called a transom plug in the bottom of the hull, which was removed when a boat was taken ashore so that any water it had taken on would drain out.

Worsham was responsible for preparing the boats and other necessary gear before students took them onto the lake. One day, a pair of girls set sail in one of the lasers, but they didn’t make it very far before their craft began to fill with the waters of the Sabine.

Worsham had forgotten to replace the plug and the boat sank, leaving it stuck in layers of mud and the two girls soaked from head to toe. The effort to pull the boat back up and bring it back to the docks took all day, which left Worsham’s boss quite frustrated.

“He made me write a complete step-by-step manual on how to set up the boats and get them ready,” Worsham said, with a laugh. “That’s how I did it and I turned it in with a very important number one — ‘insert transom plug.’”

Another of Worsham’s responsibilities was ensuring the boats were called back to shore if a storm approached.

If there was even a chance of dangerous weather rolling in, Lamar sailors were supposed to remain in the basin area close to land instead of going out into the main lake. However, not everybody listened. He recalled one set of guys whose first mistake was removing their life jackets nearly as soon as they’d departed the shore. Their second, and much larger, mistake was taking the boats deep into the main lake despite warnings of oncoming weather.

Worsham said that since the lake was relatively shallow, the waves it produced were often quite powerful. That factor, combined with the small dimensions of the boats, meant that a six-foot swell could very easily overtake a vessel and cause problems.

“These guys got out there and got caught in those swells,” Worsham said. “I got the Pleasure Island police for help and we were sitting at the seawall watching with my binoculars. It’s funny in hindsight because when the swell would come up, all you could see was just the top of the mast, and then the guys in the boat trying to put their life vests on and tie themselves to the mast.”

The police and Worsham were about to call the Coast Guard to rescue the irresponsible sailors when a 35-foot motorboat showed up and towed the smaller craft back to the dock.

“I didn’t say a single word to the guys,” Worsham said. “I didn’t have to give them a lecture or anything about boating safety, because they learned their lesson big time. They were white as a sheet.”

Worsham recalled another story which is so unbelievable it could have been pulled straight from a Hollywood movie script.

On what felt like a normal day, Worsham was closing up shop alone at the boat slips. Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed an old, wooden monohull pull up and dock several slips over. The vessel, named the Arc Taurus, had certainly seen better days.

By the time Worsham looked up from his gear, the captain of the Arc Taurus was standing in front of him — flanked by two large, burly men on either side.

“Young man, I’ve been watching you,” the captain told Worsham. “You’re a mighty fine sailor. I could use a man like you.”

Worsham said he appreciated the compliment, but he wasn’t auditioning for any jobs.

Yet, the captain pressed on regardless. He explained that he had to make a run into the Gulf of Mexico and needed an extra member for his crew, but he offered no more details about the excursion.

“I’m standing at the barge by now,” Worsham said. “If I take another step backwards, I’m in water. So, I’m standing here, and these two big burly guys come down onto the barge and start walking up to me. By now, I’m thinking, ‘Oh man, they’re getting ready to Shanghai me.’

“I said, ‘Oh my God. No.’ And of course, there’s no cell phones or anything to call for help. But all of a sudden, the guys stop and I saw their eyes get really big. Then, the captain of the Arc Taurus said, ‘Come on, men. We’ll get him out another time.’ By now, I’m just wondering what happened.”

As the captain and his men walked away, Worsham turned around. The sight he was greeted with was an old Danish sailor standing on the bulkhead of a ship behind him — pistol raised and trained on the three would-be kidnappers.

The old Dane, who lived on a sailboat of his own docked in a neighboring slip, had heard the commotion and stepped out to investigate. Having just saved the day, he invited Worsham to come sit and chat on his boat.

“That’s when he told me that he’d sailed all over the world,” Worsham said. “The Dane said he never did like that crew and thought they must be up to something, probably running contraband of some sort. He said I probably would have become shark food.

“I thanked him profusely, and he told me the same thing the others had. He said, ‘I’ve been watching you, and you’re really a good sailor. I had to keep an eye on that crew over there. But don’t you worry about them, because they won’t bother you again.”

Worsham left and went about his business, having narrowly escaped a trip to Davy Jones’ locker. When he returned the next weekend for work, he couldn’t believe his eyes.

The Arc Taurus had sunk to the bottom of its slip, the bilge pump having been unplugged. Indeed, the crew would not bother him again.

Despite the excitement which occurred at Pleasure Island, interest in Lamar’s sailing courses waned over the following years. The university stopped offering it as a physical education credit around the turn of the millennium. The 1998-2000 edition of the Lamar University catalog was the final one in which sailing was listed.

Even so, the legacy of Cardinal sailors lives on.

While Worsham hasn’t stepped foot on a sailboat in some time, he has found himself back on the water on other vessels and his love for sailing persists to this day. A placard in his house reads, “Sailing is the fine art of getting wet and becoming ill, while slowly going nowhere at great expense.”

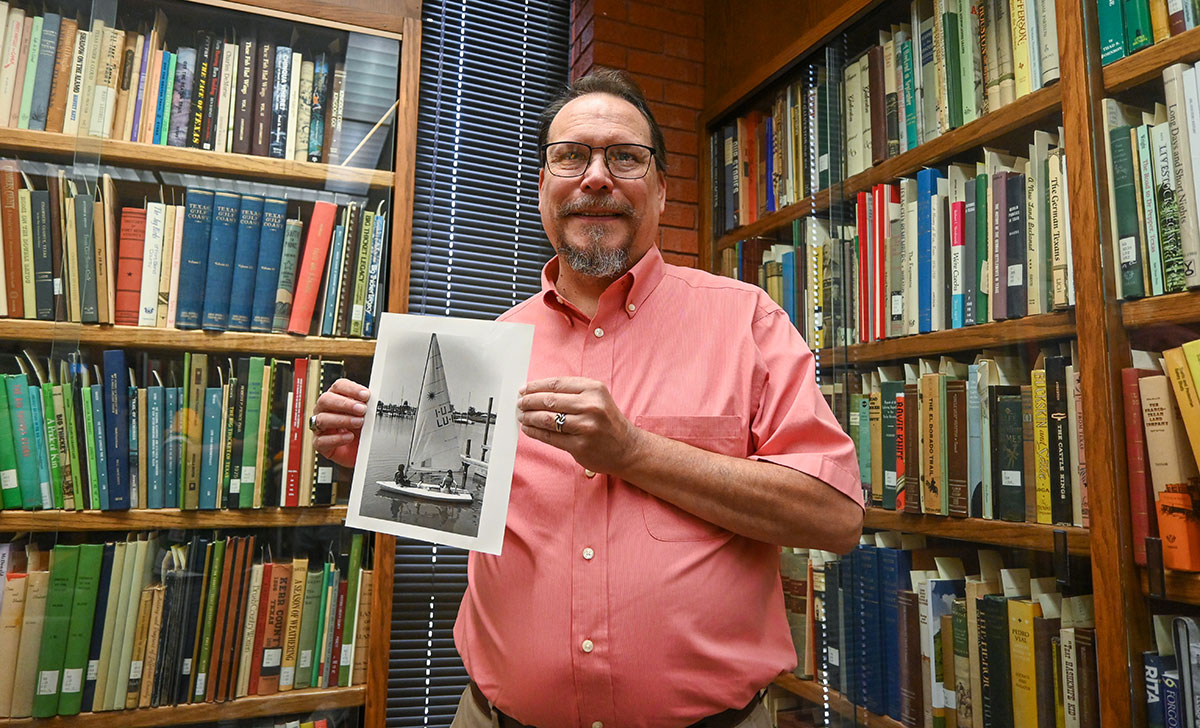

Today, Worsham works at his alma mater as University Archivist in the Mary and John Gray Library — a position which allows him to preserve the school’s history while sharing his stories with anyone who cares to listen.

As it turns out, some of the best tales aren’t buried in the library’s racks.

David Worsham, archivist in Gray Libraryholds a picture from the archives. UPbeat photo by Keagan Smith.