Wild Earth, Texas AgriLife discuss importance of flexibility, preparedness, community for livestock in wake of storms.

Tropical Storm Imelda landed on the Gulf Coast, Sept. 17. Classified as a tropical storm only shortly before landfall, the storm brought serious flooding to Southeast Texas and Louisiana.

Imelda brought more than 43 inches of rain to some areas and was responsible for four deaths and more than $2 billion in damages.

Before landfall, Imelda was forecast to bring only 12 inches of rain.

While water rescues were carried out in flooded Southeast Texas neighborhoods, local ranchers were relocating their livestock to higher ground to be safe from this unexpected natural disaster.

This flood was not Rachel Wilson’s first rodeo. As owner and operator of Wild Earth Texas on Highway 73 for eight years, Wilson has experience responding to storms.

“We got water during Imelda like everybody else,” Wilson said of her ranch, halfway between Winnie and Port Arthur. “We were fortunate enough to have enough high ground to move our cattle to.”

Wilson has weathered many storms in her career, and said each storm brings different challenges in caring for livestock.

“We had Hurricane Rita, which was a wind storm,” she said. “We dealt with Hurricane Ike, which had a 17-foot storm surge across the property. And then you get storms like (Hurricane) Harvey, where you just get straight rain coming down.”

Preparation for a storm depends on how much warning ranchers receive, Wilson said.

“You have to work with what nature gives you,” she said. “Whatever worked in the last storm may not work in this storm.

“Be adaptable — and call on your neighbors to see how you can help, or tell someone you need help.”

Wilson stressed the importance of reaching out to the community during these events.

“Our area, especially after Harvey, has developed an incredible network of cowboys and animal rescuers, and people willing to get in a bass boat and go help,” she said. “It’s like the Cajun Navy, but for livestock.”

After Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Ford Park became a medical center and evacuation hub for livestock.

“It just happened on the fly,” Wilson said. “They had animal barns there and it worked as a main hub. During Imelda that didn’t happen because I think Ford Park flooded.”

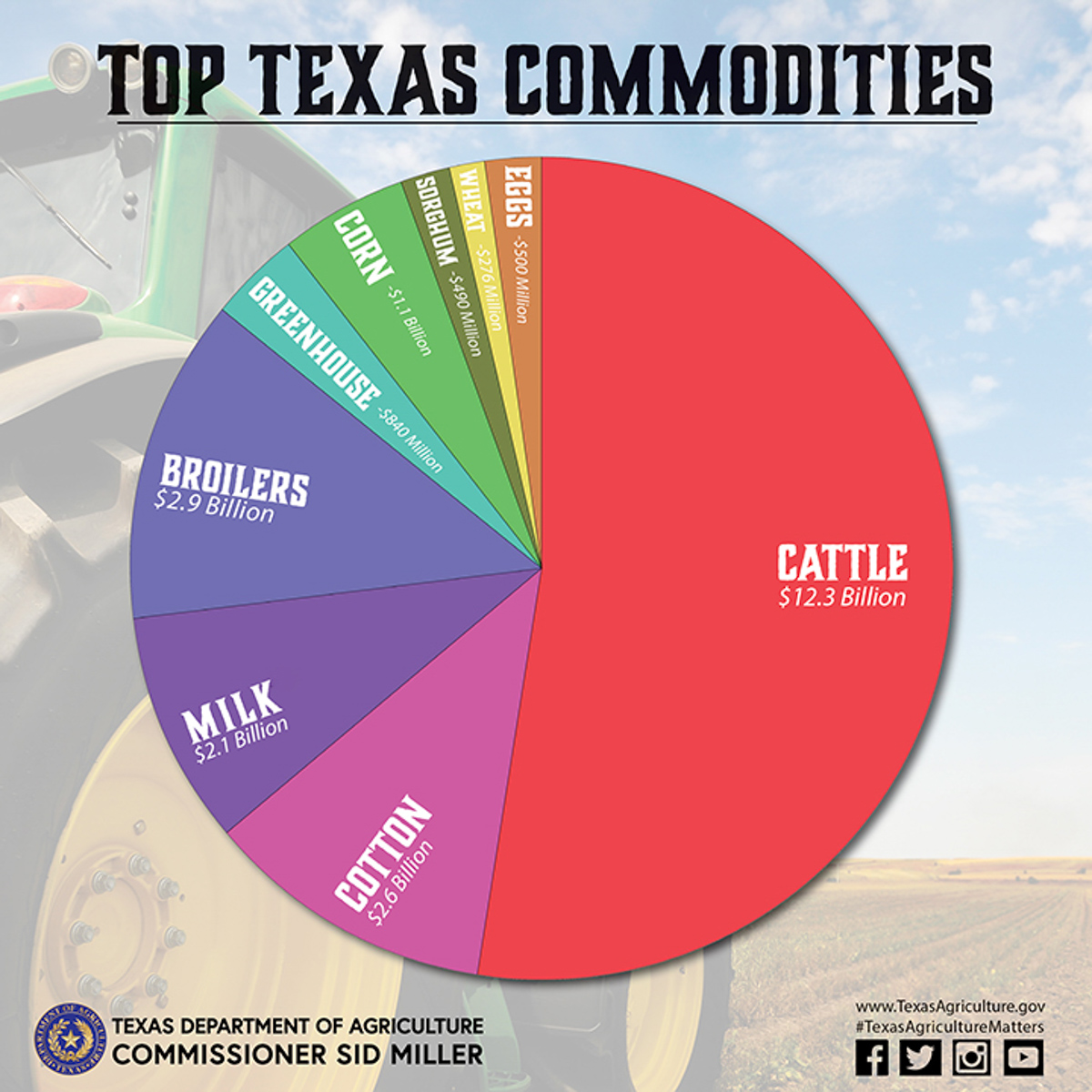

How ranchers react to natural disasters is important because cattle is the top agriculture commodity in the state. According to the Texas Department of Agriculture, Texas farms sold $24.9 billion in agriculture products in 2017. Cattle brings in $12.3 billion of that.

Imelda’s intense flooding and unpredictability was a major concern for Southeast Texans. Some areas that flooded during Hurricane Harvey didn’t hold water during Imelda. Some areas that didn’t flood during Harvey and were thought of as “safe,” flooded during Imelda.

Wilson repeated the same advice, “You have to be adaptable.”

Wilson’s infrastructure was not damaged during Imelda, but she was flooded in for about four days. While Wild Earth didn’t lose any livestock to the flood, one was struck by lightning and died.

Her neighbors on the southern end of the ranch were flooded in for 10 days, Wilson said, and had to travel by tractor and boat to reach the grocery store.

“When you have a community like that, it’s not so scary,” Wilson said. “Usually you start with calling your neighbors, and everybody knows somebody.”

Concerning the long-term effects of a storm on livestock health, Tyler Fitzgerald, Jefferson county AgriLife Extension Agent, said risks to cows include stress, access to food and freshwater, and the ability to get to higher ground.

Fitzgerald said how well a cow recovers after a flood can vary.

“A lot of it depends on the health of a cow going into (the event), how much food they have available, and how long they’re in the flood,” he said.

A storm like Hurricane Ike in 2008 was a more stressful event due to the storm surge contaminating freshwater sources, Fitzgerald said. Cows were surrounded by saltwater they couldn’t drink.

“It’s like putting a person in a boat in the ocean without a bottle of water,” he said. “Rule of thumb — a cow can go about three days without water. If they’re stressed and start drinking saltwater, it can put their whole system into shock and cause all kinds of adverse reactions.”

Freshwater floods, like Imelda, can still be stressful events for livestock, Fitzgerald said.

“They have access to water, but they typically don’t have access to food,” he said.

Many people assume cows can eat the vegetation that sticks up from a flood, Fitzgerald said, but often times that includes weeds, trees or twigs with either little nutritional value or that cannot be digested by cows.

“Availability of forage is a big thing,” he said.

If a cow has access to food and water, they still cannot stand in water for prolonged periods of time, Fitzgerald said.

“The water starts to affect their skin,” he said. “Some people call it ‘river rot,’ but it’s when their skin starts to flake off.”

Fitzgerald said it takes a few days for river rot to occur, but it can lead to serious health consequences such as infection and, eventually, death.

Cows will also become more stressed when they must be rescued from standing in water, or when they have to swim, as opposed to being able to migrate to higher land themselves, Fitzgerald said.

To prepare for a storm, Fitzgerald has similar advice to Wilson.

“Always be prepared,” he said.

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension publishes the Texas Extension Disaster Education Network, or Texas EDEN, which has a library of resources for disaster and safety. Fitzgerald recommends the “Preparing for the unexpected” section.

“When it goes from a weak, low storm to a tropical storm overnight — and then rains 43 inches — there’s no real preparedness on that respect,” he said. “You can only do so much.”

The library has information on preparedness for families, homeowners and ranchers concerning wildfires, droughts and floods.

Fitzgerald said flooding events do not have any effect on the safety of local food supplies.

“It really is not impactful because there’s so many regulations within the USDA and FDA,” he said. “So, if an animal was stressed or had any issues, they must be fully recovered before they go into the food supply.”