When an athlete goes down, whether it’s on a wet field, a dry court, or in the middle of a diamond or dirt road, the crowd goes silent as they wait to see if their favorite player, friend, son or daughter will get back up. In that moment, coaches, fans, media, family and friends do the only thing they can do — wait.

As the crowd watches, figures, usually clad in khaki shorts and collared shirts, walk to the player to assess the damage and help the athlete to their feet. Lamar University’s athletic trainers aren’t often seen or heard, but they play a vital role in ensuring athletes are healthy and taken care of from time of impact to the time of return.

Assistant athletic trainer Emlyn Ngiratmab, practices fire-cupping,

a technique used to bring blood to the surface after an injury,

can also be used to increase flexibility and revive tired muscles. UP photo by Noah Dawlearn

Emily Ngiratmab and David Kovner, assistant athletic trainers underneath head athletic trainer Joshua Yonker, have seen many athletes through some of the toughest moments of their careers.

“I feel like for a lot of us, as athletic trainers, that’s the reason why we love our job,” Kovner said. “That’s why we love doing it.”

The trainers work spans from the moment an injury happens, to the moment that the athlete returns to the field.

“Whether that’s running on the field or the court and providing emergency care, or evaluating the injury postgame or the next day in the athletic medicine clinic, and then doing treatments and rehabilitation throughout the injury until the athlete’s return,” Kovner said.

When an athlete is injured, the first person they see when they look up is an athletic trainer. Being the first person on the field can be scary and overwhelming, but both Ngiratmab and Kovner said their training allows them to be a picture of calm.

“We are so well trained, and we do so much through repetition and training that it’s almost second nature,” Kovner said. “At least for me personally, I get in the zone. Everything else is blocked out and I’m so focused. As far as being the first one out on the field and making that call whether the athlete can return or if we need to hold them out, that’s why we go to school. That’s why we’re so well versed in athletic injuries — we go through extensive training and schooling for that. We feel confident in our abilities to assess and make those clinical diagnosis and decisions — it’s through a lot of repetition in training.”

Both Ngiratmab and Kovner graduated from different four-year universities before completing their master’s at Lamar, a training program that led them to full-time jobs as assistant athletic trainers last year.

“Because of our educational background, 80 percent of the time, if not a little bit more, we can tell you what’s going to happen before it happens, or we can foresee something happening,” Ngiratmab said. “There is a lot of things that happen really fast when an injury happens. We take into consideration not just your basic how did they get hurt, but we think of the week the athletes had.

“What I love about athletic training specifically, and the medical field, is the holistic approach. We really do care about not only the physical aspect but the psychological aspects — the type of week the athlete has had and that kind of stuff. We take into consideration all of those, in addition to the injury.”

Ngiratmab said that staying calm in times of injury is key to keeping the athlete and the crowd calm.

“It’s funny, because when I look back and I think of when athletes have gone down and gotten hurt, it low-key plays in slow motion in my head,” she said. “I’ll see it and I’ll know to just give them a minute and let them just lie on the ground or if I need to get out there. But, regardless, one thing that is pretty common in the athletic training field, is very seldom will you see an athletic trainer run towards an injury unless it’s football, just because of the size of the field. Most of the time, when someone goes down, we have to be calm, because if we run in there people will be like, ‘What’s going on, what’s going on?’ In those moments, we definitely don’t panic. Yes, our mind goes through all the things that could be and what we need to do in the series of what needs to happen, but we definitely have to be the sense of calm in the scenario, because the athletes are down, the coaches are worried, the players and the fans, and all eyes are on you in that moment. We have to make sure we’re carrying ourselves in a way where we’re bringing calmness to the situation.”

During the time between the initial injury and the athlete’s return, the trainers are working full time around the clock to help the athlete heal and return to play as soon as possible. A process which requires a lot of time and effort, Ngiratmab said.

“Another cool part about athletic training is that we don’t just deal with it when the injury occurs, we see when they actually come in and we try to correct and do preventative medicine,” she said. “Whether that’s ACL preventative or if they come in with a history of back issues. We definitely get to know each individual athlete regardless if it’s an entire football team or it’s the men’s or women’s golf team. It doesn’t matter how many there are, we take the time to get to know them for all those things.”

Kovner said his main job is to take care of student-athlete welfare above all else, even if that means holding back the time of return.

“If, for any reason, the injury that they sustained can either become worse or cause them to injure something else, our main goal is to make sure that the student-athlete’s welfare is kept,” he said. “So, if that’s our call to pull them from participation, that’s what we’ll do. We don’t just look at the immediate welfare, we will also look at long term.

“Say the athlete has an ankle injury that they have been rehabing and we don’t feel that they are ready to return to the field, but they do feel that way. We are going to hold them out because we don’t want them to go out too early and re-injure themselves, and then have ankle issues for the rest of their life. We look at the long-term approach as well as short term. We still want to get them back on the field as quickly as possible, but in a way that keeps their welfare intact.”

Ngiratmab said it can be difficult to reason with an athlete who is eager to return to their sport when they are in the middle of the season.

“Typically, when an athlete is in season, the demand of return to play is a lot quicker,” she said. “If they are in season, if they get hurt in the game, they will have to see us immediately after. We will do some type of treatment, kind of tell them what to expect, what they need to do that night, and then they will have to come see us before class or between classes the next day. Then, in addition, they will have to see us again before practice depending on if they’re participating in practice or if we have to modify their workout. They may be allowed to do a few of the drills, non-contact drills, or that kind of stuff. We will make those modifications as needed and then they’ll still have to see us after practice.

“So, we get in contact with them multiple times throughout the day. Not just that, but we work very closely with our coaches, and our strength and conditioning coaches. So whether it’s an ankle injury, a knee injury or a shoulder injury, we do things to keep them training, but in a way where we’re not worsening the injury or irritating it, but to allow them to enable to keep their level of training. It’s all about being adaptable and understanding the demands, but also keeping in consideration their welfare.”

Kovner said getting to know the athlete helps in the treatment process and allows a foundational trust between trainer and student.

“We have degrees in athletic training, kinesiology or exercise science, and then we go and take our national certification exam and become nationally certified,” he said. “What those programs do is they give us a basic foundation of knowledge of how to manage an injury from evaluation to diagnosis to treatment to prevention. We have that basic knowledge of how to treat, but we get to know these kids very well, from the moment they come here as a student athlete to the moment after they leave.

“We know what they like to do in treatment, we know what they don’t like but still need to do in treatment, and we work with that. We also take into consideration their class schedule. They are student athletes — students first. So we won’t only have one time in the day to do training, we can work with the student athletes to find the best times for them. It’s a lot of give and take, a lot of working with them as people. They’re not just athletes, they’re people that we work with — it’s very personable and personalized.”

Ngiratmab said the athletic trainers are “forever students,” and are always learning new methods and techniques to keep their patients healthy and up-to-date.

“Treatment options are always growing and always getting better, or something can progress and get better,” she said. “Not only do we have that foundational knowledge, but we also continue to follow certain protocols — understanding the healing process, the physiological effects, immediately after an injury, 72 hours after an injury and three weeks after an injury, and just knowing how to adjust our rehab and treatment and progression and get them back.

“The cool thing about being an athletic trainer at this time is the internet and social media. When other healthcare professionals come up with something new, they post it, they talk about it, so it’s easier for us to attain that new information, which is kind of cool. When an athlete sees an NBA player doing this rehab exercise, and all of a sudden they see us doing it in here, they get excited to do it.

“It’s a challenge. It’s something that kind of keeps them motivated to come (to rehab), because when we spend as much time with them as we do it gets tedious. We definitely try to match their personality and give them something exciting, get them something to work towards a goal.

When an athlete gets injured, they can get depressed about being unable to play. Ngiratmab said the trainers try to channel the athletes natural competiveness.

“They’re all competitive, so it’s like, ‘I bet you can’t do this,’ ‘Bet you can’t do another set,’” she said. “Now, it can become something exciting, because they’ve met a goal in rehab and then they understand the bigger picture of things.

“It’s not just the injury, it’s treating the psychological aspect as well. You could be healed after an ACL surgery, but to get back into the game, that’s the biggest battle, right? It doesn’t matter what your body is ready for, if your mind is hesitant, then I’m not comfortable putting you back in, because that’s where injury occurs. Psychology is such a big aspect, so through rehab and injury, we are also kind of feeding into them their confidence and reminding them, ‘Hey, we’re going to work through this, but remember when you struggled with this a couple weeks ago, now look at you.’”

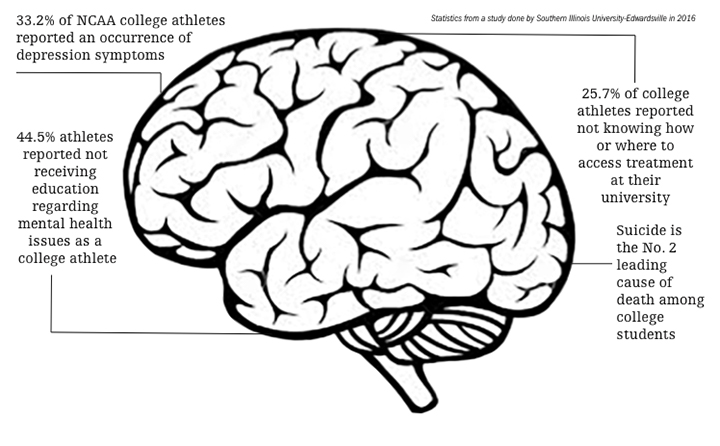

Ngiratmab said after seeing several athletes injured across different sports last year, she noticed a pattern of mental health issues.

“I think, for me, each year something different has stood out to me — this year, the biggest thing that I realize I want to learn more about mental health,” she said. “There has been a pattern of different mental health issues that have happened this year, and as athletic trainers, we have that foundational knowledge to know enough that something is going on. We spend enough time with athletes to know there are red flags.

“Unfortunately, and I’ll admit it, it’s something I want to know more about, because I don’t know where to go from there besides referring them to a counselor. But this year has made me realize that I want to do more research to know how to handle those situations. I found myself frustrated a lot, and it’s not just with one sport, it’s been across the board. Regardless of the athlete, the common factor has been mental health battles, and not just with injuries, but with life. That something I want to be better at and emphasize.”

Kovner said he also sees more occurrences in the mental health of his athletes.

“I’m not sure if it’s just more common these days, or if my foundation of knowledge has grown and now I’m just able to recognize it better,” he said. “medicine is forever growing, and as a medical provider, I’m always looking to improve myself and get better at what I do, and mental health is on the top of my list — being able to provide more care for someone who has a mental disorder.

“We could refer an ankle injury to an orthopedic physician, but because my foundation of knowledge is so strong with that, I am able to progress an athlete from time of injury to return of play. I want to be able to do the same for any type of injury, and that takes in to account the psyche-social aspect as well.”

Kovner and Ngiratmab both said nothing feels better than after the long process of healing and training, than to see an athlete return to play. A feeling that makes the hard work they do worthwhile.

Ngiratmab said the deeper she got into athletic training, the more she understood what athletic training does — everything.

“We can adapt — we can go anywhere and be anything,” she said. “Each time, I have just fallen more in love with what we do — even through the hard times. It has definitely made me realize that this is what I am supposed to do. This is the type of impact I want to have on people.”

Ngiratmab graduated from Sterling College in Kansas before receiving her master’s in kinesiology in 2015 at Lamar, and earned a secondary master’s in nutrition before becoming assistant athletic trainer at LU. She oversees cross country, track, volleyball and tennis, in addition to being the clinical coordinator for the athletic training apprenticeship program.

“It’s funny, because when I left my undergrad, I told myself two things,” she said. “I was going to move closer to California and I wasn’t going to go to a Division I school — and it’s the opposite. There have been tough times. There have been times where burnout gets real, especially making that transition from being a student to being certified. But, one thing I have appreciated the most about Lamar is our staff. (Head athletic trainer) Joshua Yonker, the type of mentor he has been in my career, especially post grad, I don’t think he realizes the depth of the type of mentor he has been. In addition to that, the staff that has been here as I was a graduate assistant, they have been crucial mentors, too.

“It’s really the people you work with that make the vision that we have worth working harder towards. We want to exceed expectations, because we all have people who have that same vision. My experience here has never been one I could have planned or imagined, but it has been one that I know has shaped me remarkably.”

Kovner received a bachelor’s in athletic training from Stony Brook University in Long Island, NY, before transferring to Lamar to receive his master’s in kinesiology. During that time, he was a graduate assistant athletic trainer in the athletic medicine department under Yonker and alongside former classmate, Ngiratmab. After his graduation in 2017, he became a full-time assistant where he oversees men’s and women’s basketball, golf, softball, baseball and soccer and also assists with the athletic training program in teaching courses.

“It’s unique,” he said. “Not everyone gets to return to their alma mater and work full time with your former roommate and colleague. It’s definitely a unique position, and it’s something that I am forever grateful for and love. It’s about the people you work with. The job title and everything else is great, but it’s the people that make it all worthwhile.”

To learn more about the athletic training program at Lamar, visit the health and kinesiology page at lamar.edu, email josh.yonker@lamar.edu, or call Kovner or Ngiratmab at 880-7394. Or visit the Dauphin Athletic Complex located next to Provost Umphrey Stadium.