Thirty-one years after leaving her childhood home, C. Brennan still feels the physical and psychological trauma left behind by her father, an alcoholic who tormented her, her mother and her siblings.

“He was someone who was beloved by his family, and respected socially and in his career,” Brennan, now 51, said in an email interview. “He was a monster only at home. His behavior was sometimes intimidating in public but not in any way comparable to his behavior at home.”

Brennan, who grew up in Southeast Texas but now lives in New mexico, said that although her father did not physically abuse his children, he psychologically harassed and shamed them while maligning their mother, whom he also physically and sexually abused.

“The physical and sexual abuse was perpetuated without any attempt to hide it from his children,” she said. “He began beating my mother almost as soon as they were married, so my entire childhood was punctuated by the sounds of his guttural abuse and my mother’s terrified screams.

“The sounds of his fist pummeling her flesh and her body being thrown into walls were the earliest things I remember — that and my mother’s face being swollen from punches and eyes almost swollen shut from crying.

“As the children of an alcoholic, my siblings and I were expected to hide all traces of his alcoholism and abuse, so that we lived a sort of schizophrenic experience.”

When Brennan and her siblings reached out to their grandparents, their stories were not believed.

When Brennan and her siblings reached out to their grandparents, their stories were not believed.

“I do not remember a time that I did not recognize (that) what my father was doing was not right,” she said. “At the ages of two and three, my sister and I described my father knocking my mother, pregnant with my brother, down the stairs and kicking her in the stomach.

“We also described certain sexual acts we should not have seen. The people we told did nothing. No one ever intervened.”

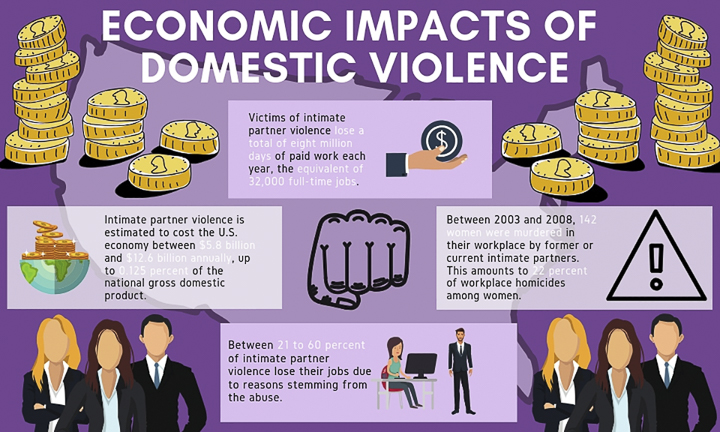

Brennan’s story is not uncommon. In the United States, an average of 20 people experience intimate partner physical violence every minute, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. This equates to more than 10 million victims annually.

“The reason that people are abusive is because they want power and they want to maintain power,” Marie Murray, assistant director for health education services at the Lamar University Student Health Center, said. “The reason that this happens is because it’s kind of in our nature to want control over certain situations.

“There’s a lot of different things. You have people who are abusers because they were abused themselves, and so now they want power back in their lives that they didn’t have before. Then you just have people who their personality type is just that they want power and control.”

Brennan said that her father grew up in a loving environment, but that he, too, experienced trauma in his childhood.

“(He spent) 18 months in a Shriner’s hospital,” she said. “We don’t know everything that happened to him then, but he was deeply misogynistic, deeply wounded and extremely selfish in relationships.

“He was narcissistic and probably had sociopathic tendencies. None of that was ever addressed. My grandmother carried the guilt and shame of that unspoken thing that happened. My father was also molested by a scout leader when he was a boy. So, perhaps every abuser has a similar story.”

Emotional abuse leaves a scar, too

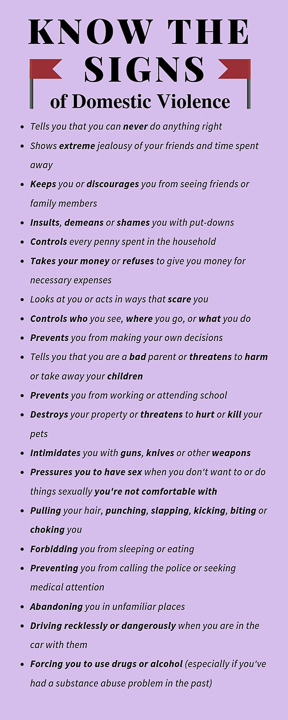

Physical abuse can be seen on the outside, which leads people to believe that domestic violence only consists of hitting and kicking, etc., but Murray said that emotional abuse is just as common and can have the same lasting effects.

“(There are) a lot of warning signs for emotional abuse,” she said. “Somebody can be really intense or jealous — these things don’t always lead to physical abuse, but they can.

“Manipulation is a big one, because someone can manipulate someone else without ever having to raise a hand against them. A lot of times, for women who are abused, the abuser might use their children as a way to manipulate them — it may never be that they harm them, but are constantly under the threat of harm or taking them away.”

Murray said that often times, when abusive relationships occur and the victim is an immigrant, the threat of deportation is used as means of manipulation.

“Isolation is another (warning sign),” she said. “By keeping people isolated from their friends and family, that physical isolation can lead to mental isolation.

“Sometimes in a victim, you’ll see a dramatic shift in their personality — someone who used to be happy and bubbly might become very withdrawn, and they’re not open to telling people anything because they’re afraid or their abuser made them feel worthless and that they shouldn’t confide in anybody.”

Kaleb Dixon, Lamar State College-Orange alumnus, was in an emotionally abusive relationship for six months, which he said left him depressed and feeling worthless.

“I was at work one evening and I met this girl who was sitting alone, and I approached her and we were talking about our interests — the way relationships typically start,” Dixon, 22, said. “We took it kind of fast and we ended up living together after just a few months. Looking back, it wasn’t the best decision on my part, but she wasn’t very familiar with the area because she was from a different state and I wanted to show her around.”

Dixon said people don’t always understand that it’s difficult to predict which relationships will become abusive — that it’s more of a gradual realization.

“It took me a while to really pick up on the signs of abuse in my relationship,” he said. “Being a man made it a little bit more difficult for me to understand the tell-tale signs of stuff like that, because I think that a lot of times men are expected to be the provider, to be the person who provides emotional support to those who need it. So there wasn’t really an opportunity for me to voice my concern when I wasn’t feeling great, or if I didn’t understand something or if I was having a bad day — there was no comfort there, it was just like, ‘Well, why don’t you care about me?’”

Eventually, Dixon left the relationship, but only temporarily.

“A few weeks later, I get a text message from her phone and her mom texted me with a couple of pictures and told me (my ex) had been in a car accident,” he said. “I didn’t know if she was going to make it, and I took a step back and decided that I’d go back and take care of her.

“I slowly but surely moved back into the apartment and took care of her while she was still being super mean to me, and that was probably the hardest experience I’ve ever had to deal with, taking care of someone that didn’t really want me there, they just wanted attention.”

Dixon said the abuse was physical at times, and about a month after his girlfriend’s car accident, he left for good.

LUPD Sergeant Jarrod Samford said that men are less likely to report abuse because of the notion that men aren’t supposed to be the victims of these situations.

“They’re afraid to be judged and it’s this whole other level of judgement, so it’s a psychological battle that they’re going through to come forward,” he said. “Violence is violence, no matter which side of the equation you are on.”

Reach out for help

Both LUPD and the Student Health Center have steps in place to assist students who may be victims of domestic violence or suspect that their friend or family member is suffering.

“For someone who might be trying to leave an abusive relationship or has come to the realization that they are in one, they can come to the Student Health Center and seek help,” Murray said. “There are counselors here, a confidential source for someone to talk to — they may not be ready to leave their relationship yet, but they can come in and talk and know that it’s going to be confidential between them and the counselors.”

Murray said that statistically, everybody is bound to know somebody that’s affected in some way, shape or form by domestic violence. She said that people need to take the initial step of helping those in abusive situations, but that holding themselves accountable by following through is the second step to stopping abusive relationships.

“We all say, ‘Oh yeah, we’d be the person to step in,’ but then we don’t,” she said.

Samford said LUPD is on campus to assist students in anyway they can.

“A healthy relationship should not hurt. No matter how bad things are, they will get worse as long as you allow it to continue.

“We are here because we care about the students, faculty and staff of Lamar. Our job is to make sure everyone is safe. There is no judgement here.”

Next week, The Aftermath — the impact of domestic violence on its victims.

If you or someone you know is in an abusive relationship, contact The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-3224, or visit their website at www.thehotline.org for more information.

Students can make appointments at the health center by calling 880-8466, emailing dept_healthcenter@lamar.edu, or by visiting www.lamar.edu/